Raw Vision

…and Outsider Art

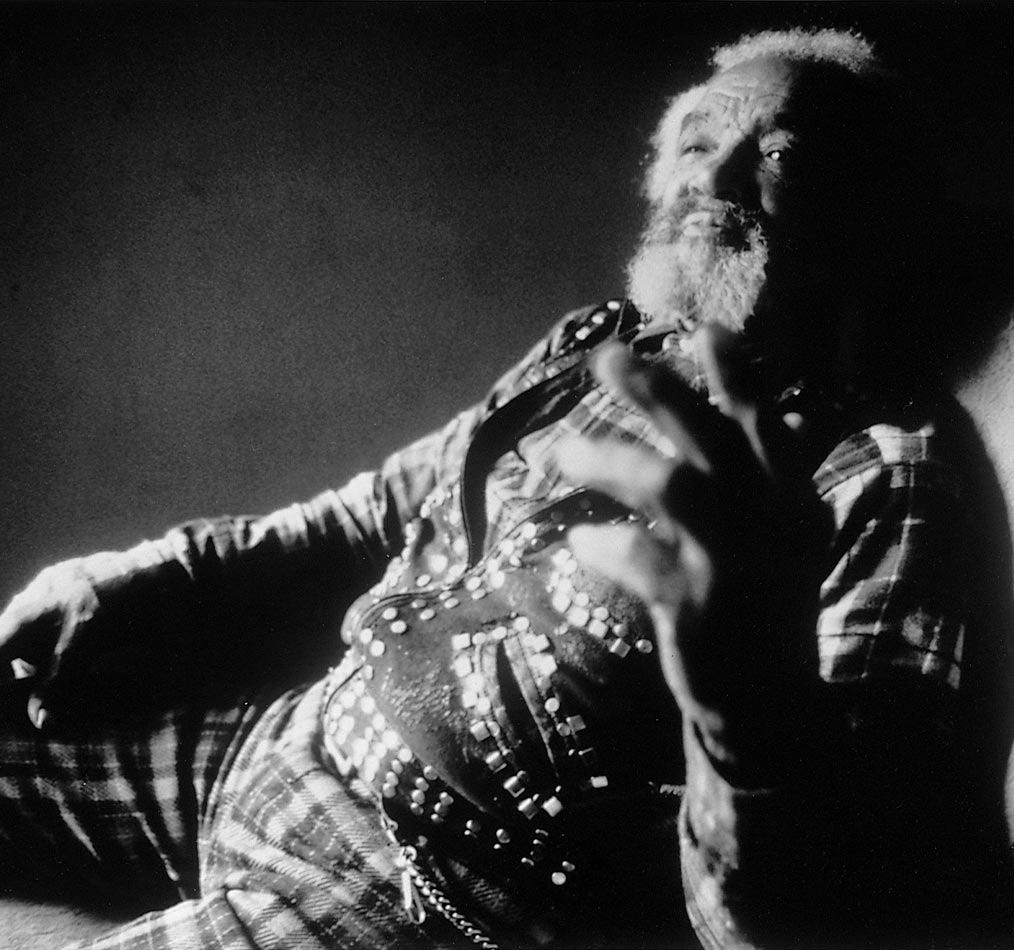

Picasso was one of many famous artists who started out in a more realistic painting fashion and after many years was able to break down his technique to a more original and individual way of expressing himself in paint (and other forms). For a man like William L. Hawkins (1895-1990), who had no previous experience as an artist, he came out of the chute in his late 70s with an original vision and unfettered energy in place. He worked without letup to the grave, in spite of illness and advancing age.

At first, Hawkins painted on plywood and discarded wall paneling with enamel housepaint in primary colors—which he salvaged from a local hardware store. Later, he worked on Masonite, which he preferred because he liked the way the paint "set up" on the surface. He painted with a single brush, whose bristles were almost down to the ferrule, wiping off each new color with an old rag. "I don't need but one brush," he would say. Hawkins poured and dripped paint—often directly from the can—letting it flow across the surface as he tilted it. Once, when Frank Maresca and Roger Ricco (founders of the Ricco/Maresca Gallery in New York City) were watching him work, he looked up and said: "See dat, boys? the paintin's makin' itself."

For more information of his life and art, check out this essay by Lyle Rexer that originally appeared in Raw Vision 45 (Winter 2003-04).

And I thought it would be most appropriate to include a couple Dave Hickey paragraphs from his book Air Guitar:

So, I have always wanted to tell this story, because it is a true story that I have carefully remembered, but frankly, it is a sentimental story, too – as all stories of successful human society must be – and we don't cherish that flavor of democracy anymore. Today, we do blood, money and sex – race, class and gender. We don't do communities of desire (people united in loving something as we loved jazz). We do statistical demographics, age groups, and target audiences. We do ritual celebrations of white family values, unctuous celebrations of marginal cultural identity, multi-ethnic kick-boxer movies, and yuppie sitcoms. With the possible exception of Rosanne, we don't even do ordinary eccentricity anymore. In an increasingly diffuse and customized post-industrial world, we cling to the last vestige of industrial thinking: the presumption of mass-produced identity and ready-made experience – a presumption that makes the expression, appreciation, or even the perception of our everyday distinctions next to impossible.

And, finally, American business stopped advertising products for what they were, or for what they could do, and began advertising them for what they meant – as sign systems within the broader culture – emphasizing what every collector wants to know: who owned them and where they were owned. Thus, rather than producing and marketing infinitely replicable objects that adequately served unchanging needs, American commerce began creating finite sets of objects that embodied ideology for a finite audience at a particular moment – objects that created desire rather than fulfilling needs. This is nothing more or less an art market. If you don't think so, price out a 1965 Ford Thunderbird.

And now…

This does bode well for the planned launch of my painting career in 6 years...

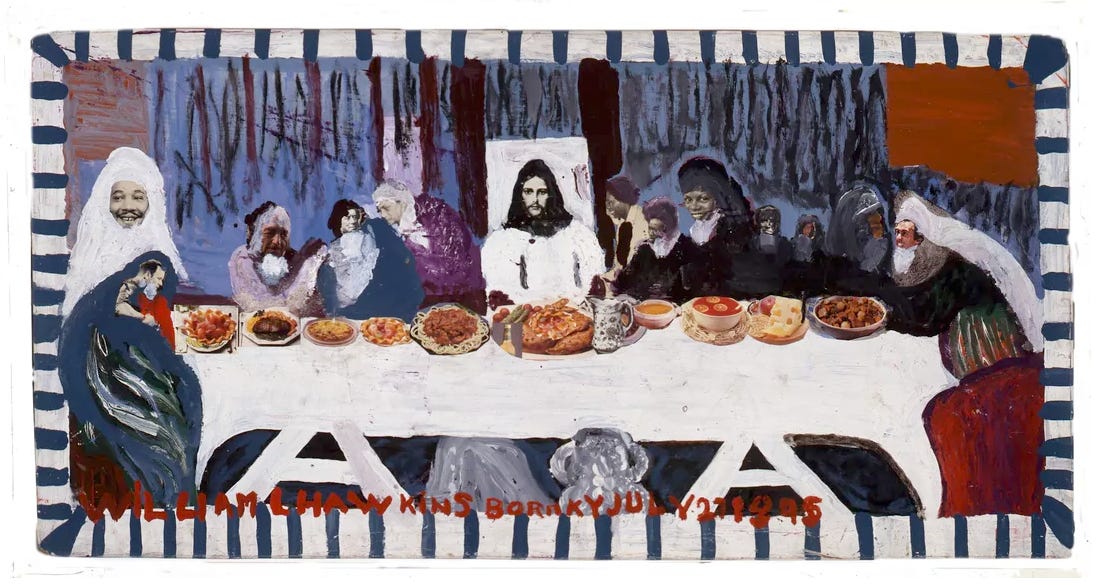

I must say Hawkins ain’t much my cup o tea, but the snake and especially the Last Supper spoke to me!